Table of Contents

- Brief Synopsis

a. Common mistakes - 24-Hour Course

- Objective

a. Vitals

b. Intake/Output

c. Physical Exam

d. Electrolytes

e. Relevant Imaging - Assessment and Plan

- Checklist Manifesto

Brief Synopsis

Whether or not this is a necessary thing to do, I always start my MICU progress notes with a summary of the events that have occurred since hospitalization. I will update this section when significant events occurred.

Example: This is a 46-yo F with a history of type 1 diabetes who is on day 1 of hospitalization and presented with nausea and vomiting. On presentation, the patient was found to have an anion-gap metabolic acidosis with ketonuria and was admitted to the MICU for management of diabetic ketoacidosis with insulin gtt, and frequent lab draws. Since admission, her anion gap has closed and was bridged with subcutaneous insulin.

I think if a resident can summarize the chief complaint and what we are treating, then ICU becomes a heck of a lot easier. When you struggle on your ICU rotation, remember to ask yourself, “what are we treating” and “why is this person sick?”

Common mistakes

- Copying and pasting incorrect information

- Not updating important events that took place

- Listing out every possible past medical history that is not relevant to the case and fluffing the sentences

24-Hour Course

In this section, I like to add everything that has happened over the last 24 hours. I write out my 24-hour events the same way every single time.

- Subjective: What the patient said, what the nurse said, any events overnight)

- Vitals: Are they hemodynamically stable? If not, how is their hemodynamics managed?

- Example: Patient remains afebrile over 24 hours, requiring Levophed 15 mcg and vasopressin for hemodynamic support.

- Example: Patient remains afebrile over 24 hours, requiring Levophed 15 mcg and vasopressin for hemodynamic support.

- Intake and Output: This is especially important for ICU patients as they are critically ill and, more times than not, if ignored, can easily become under or over-resuscitated. Please obtain accurate intake and output every single day.

- Labs: I do not list out values; I state what those values mean.

- Example 1: Instead of writing Na+ 121 with an osmolarity of 230, I will write hyperosmolar hyponatremia.Example 2: If the values are significant, like renal functioning, and we are trending the values, sometimes I will write out relevant information only. Side note: You will lose your attending if you just rattle off and list a bunch of lab values. This can be done in the lab section if you wish to reiterate the significant lab findings.

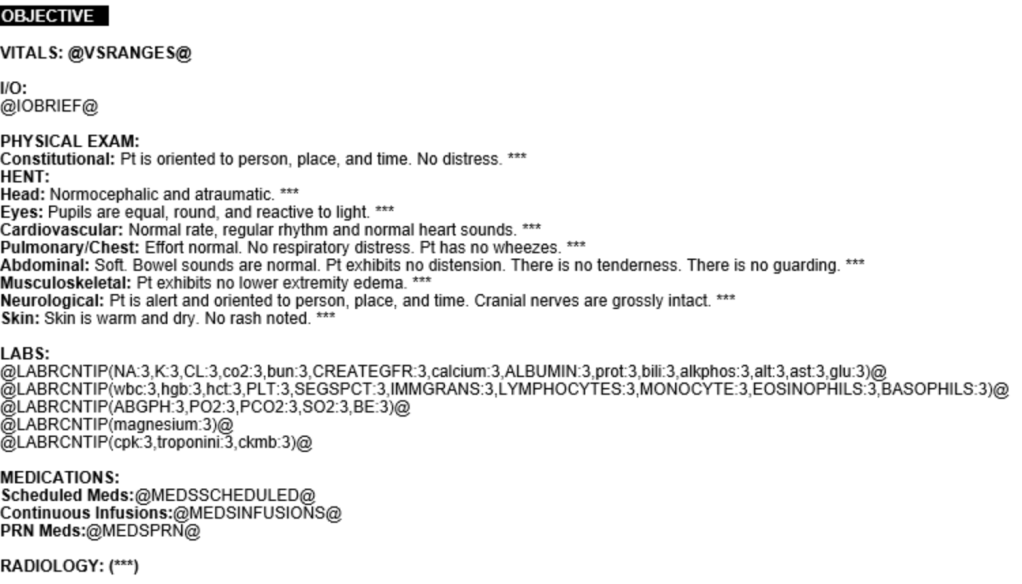

Objective

Vitals

Record vitals over 24 hours. Ensure you indicate episodes of tachyarrhythmias or bradyarrhythmia. Not the times when vitals change. Consider why those values are changing (i.e., is the patient agitated, is the patient in pain, do they have a lead wire that accidentally activates the SA node?)

Intake/Output

In brief, I want to reiterate the importance of fluid balance in the ICU. Once again, one needs to ask themselves, “where is the fluid going.” If you notice that your patient is +15 L and cannot be weaned from the ventilator, chances are there is a problem, which is wet lungs, for example.

Physical Exam

You can still do a complete physical examination on an ICU patient. For example, if a patient is sedated and intubated, a neurological exam can still be performed. Please check the pupillary, corneal, gag, respiratory, and other reflexes every morning. This is essential in patients who have been ventilated for more than a few days.

Electrolytes

I want to briefly touch on the importance of electrolyte balance in critically ill patients, especially when uncommunicative.

- Sodium: Ensure the patient is receiving enough water to prevent hypernatremia (more on this topic later)

- Potassium: Values should stay above 4 mmol/L to 4.5 mmol/LMagnesium: Values should be >2 mEq/L

- Phosphorous: Looking at these values is especially true in our patient population, where the majority are from a nursing home fed through PEG tubes. Thus, one must be aware of refeeding syndrome and should ensure phosphorous levels are adequate.

Relevant Imaging

List out any relevant imaging that will help round out the case. A common mistake I hear is when someone reads aloud an impression from a radiologist without first trying to make their own impression regarding the imaging. You are not expected to be a radiologist, but at least make the effort to look at the images.

Assessment and Plan

Very different than a typical ward patient hospitalist patient. If you have ever been on pediatric rotation, it is similar in that ICU patients are assessed by systems. Why? Because patients in the ICU have multiple systems involved and must be addressed so that nothing gets overlooked. Get in the habit of writing your notes the same way every day. This will allow your brain to think in an organized fashion. Below is a sample of the template that I follow.

Neuro:

#Diagnosis*

Assessment

- Plan

Example

Neuro:

#Hepatic encephalopathy

His wife reported he was sleeping more often during the day before the presentation. He is AAO x 1, appears disoriented, and has asterixis.

- Insert NG tube for medication administration

- Ordered lactulose 30 mL tid via NG tube to titrate to a total of 3 bowel movements per day

Below I listed out a sample of the template that I use to help me to remember to add details where it is needed while modifying it to look like the above.

Neurology:

- Current RASS: ***, RASS goal: ***

- Brain stem reflexes: ***

- Sedative requirements: ***

- Pain management: ***

Cardiology:

- Cardiac rhythm: ***

- HR/BP: ***

- Vasopressor requirements: ***

- MAP goal >65 mmHg

Pulmonary:

- Option 1: Patient denies SOB, lungs are clear to auscultation, no acute findings of CXR.

- Option 2: Date Intubated: ***; Patient is on mechanical ventilation with mode setting ***, ABG: ***

- MAP goal >65 mmHg

Gastroenterology:

- Option 1: Patient is on *** diet

- Option 2: Tube feeds via *** with *** at *** cc/h.

Nephrology/Electrolytes:

- Intake: ***/Output: ***/Net: ***

- K+: ***

- Mg2+: ***

Infectious Disease:

- Abx: *** day ***/***

Endocrinology:

- TSH: ***, Hga1c ***% on ***

- Insulin regimen: ***

- BG goal <180 mg/dL

Hematology:

- ***

Checklist Manifesto

THE CHECKLIST IS ESSENTIAL! Please do NOT copy and paste this section. Copying and pasting notes are okay to a certain extent but be reminded if you copy and paste material that is not up to date, this can be detrimental to a patient’s care. In addition, if your note is used in court, you may be deemed unreliable as an author if the notes do not reflect your care.